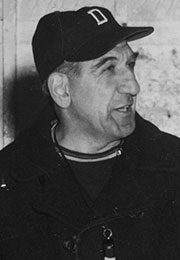

Eddie Jeremiah – 2008 Legend of College Hockey

BY JACK DEGANGE

When Dartmouth searched for a hockey coach in 1934, Eddie Jeremiah didn’t get a look, much less an interview.

At the time, Jeremiah was 29. He had graduated from Dart¬mouth in 1930, lettering in football, hockey and baseball, and winning All-America recognition on the first team to play in Davis Rink. He had played some professional hockey and was working at the old Boston Garden and coaching the Boston Olympics, the Garden’s amateur hockey team.

Three years later, the word around Main Street in Hanover was, “There’s trouble in the hockey woodpile.” Dartmouth was looking for a hockey coach—again.

In 1937, Eddie Jeremiah got a look—and the job. Maybe it was because his coaching credentials had been established: In 1936, the Boston Olympics won the national AAU championship.

He inherited a team that, in 1936-37, had a 12-13 record and a lot of bad habits. He signed a “trial” contract that was torn up three times. A record of 18-4 in 1937-38 and 17-4 a year later pro¬vided ample proof that the “Jeremiah Era,” spanning three decades of Dartmouth hockey, was off to a flying start.

In many respects, from 1937 until he retired in 1967 (he died of cancer three months after he coached his last game), Jeremiah personified the spirit of athletics at Dartmouth.

He was a teacher: His books on hockey fundamentals and strategy became bibles for coaches and players at every level. Said Roger Conant ’40, a sophomore on Jeremiah’s first team, “I learned more tricks of the trade in one season under Jerry than all my other coaches put together.”

He was a coach: “Look up and keep fighting” was the credo he instilled in his teams that won 300 games over 26 seasons. Under Jeremiah, Dartmouth was the mythical national champion (21-2) in 1941-42, played for the national title in the first two NCAA tournaments in 1948 and 1949, and won nine champion ships in the Ivy League and its predecessor leagues. Dartmouth’s 1963-64 skaters won a tenth title under Acting Coach Abner Oakes while Jeremiah coached the U.S. Olympic hockey team.

Above all, Jerry was a gentleman. During his years at Dartmouth, he also coached baseball and football. His spirit and humor influenced the lives of countless Dartmouth men. In an era of legendary, long-term coaches on the Hanover plain—Tom Dent, Harry Hillman, Doggie Julian, Tony Lupien, Ellie Noyes, and in later years Whitey Burnham aoc’ Bob Blackma—mention of Dartmouth athletics brought one name to mind: Eddie Jeremiah.

Ernie Roberts, Dartmouth’s sports information director in the early 1960s, tells the story of how coincidence shaped the history of hockey at Dartmouth.

Edward John Jeremiah won nine letters in three sports at Somerville (Mass.) High. At graduation ceremonies in 1924, a teacher asked the son of impoverished refugees from the Turkish oppression in Armenia if he’d be interested in a bookkeeping job with a company that made corsets.

“In an instant,” Jeremiah recalled, “my future whirled before me—chained to a stool poring over corset and brassiere accounts.” He gulped, “No thanks.” He ran to his high school coach and said he wanted to go to college. The coach helped Jerry get a scholarship to Hebron Academy where he took the college prep courses that earned his admission to Dartmouth in 1926. An undergarment business’ loss was college hockey’s gain.

There are few eras in hockey at any college that compare with the one molded by Jeremiah. He was blessed with talented players: seven would join him in the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame and 12 would play on U.S. Olympic hockey teams.

His coaching skills rubbed off, especially on Jack Riley ’44, who had a long career at West Point and coached the U.S. Olympic team to the gold medal in 1960; Bill Harrison ’44, who led Clarkson from 1948-58 and then had a long career as an engineering professor; and Dick Rondeau, who coached at Holy Cross and Providence for many years.

Over the years, Jeremiah served on every committee and received every award that mattered in the world of intercollegiate hockey. In 1951, though his team had a middling 9-9-1 record, he •won the first College Hockey Coach-of-the-Year Award.

He had great teams, good teams and his share of squads that finished somewhere in the pack. To Jerry, they were all the same: Teams that looked up, kept fighting and played 60 min¬utes of “heads-up” hockey.